He was bright and his name, Ishaq, was the Arabic version of the famous scientist’s first name, Isaac. He was among the best students in his school, having scored 98.4 per cent in Class X. His Class XII score, 85 per cent, was way lower, but for his friends in Laribal, a small village near the town of Tral in Kashmir’s Pulwama district, Ishaq remained Newton.

The 19-year-old was preparing to be a doctor and was studying for the common entrance test when he left home.

His mother Rehti Begum calls him the “perfect boy” who would help his elder brothers in the fields, would object to his father speaking loudly on the phone and would never ask for money.

On March 16, “for the first time”, Ishaq asked his father, Mohammed Ismail Parray, a retired government employee, for money — Rs 1,000 to pay as fees at the computer center he had joined. That was the last time they saw him. In April, the police informed them that Ishaq had joined the Hizbul Mujahideen.

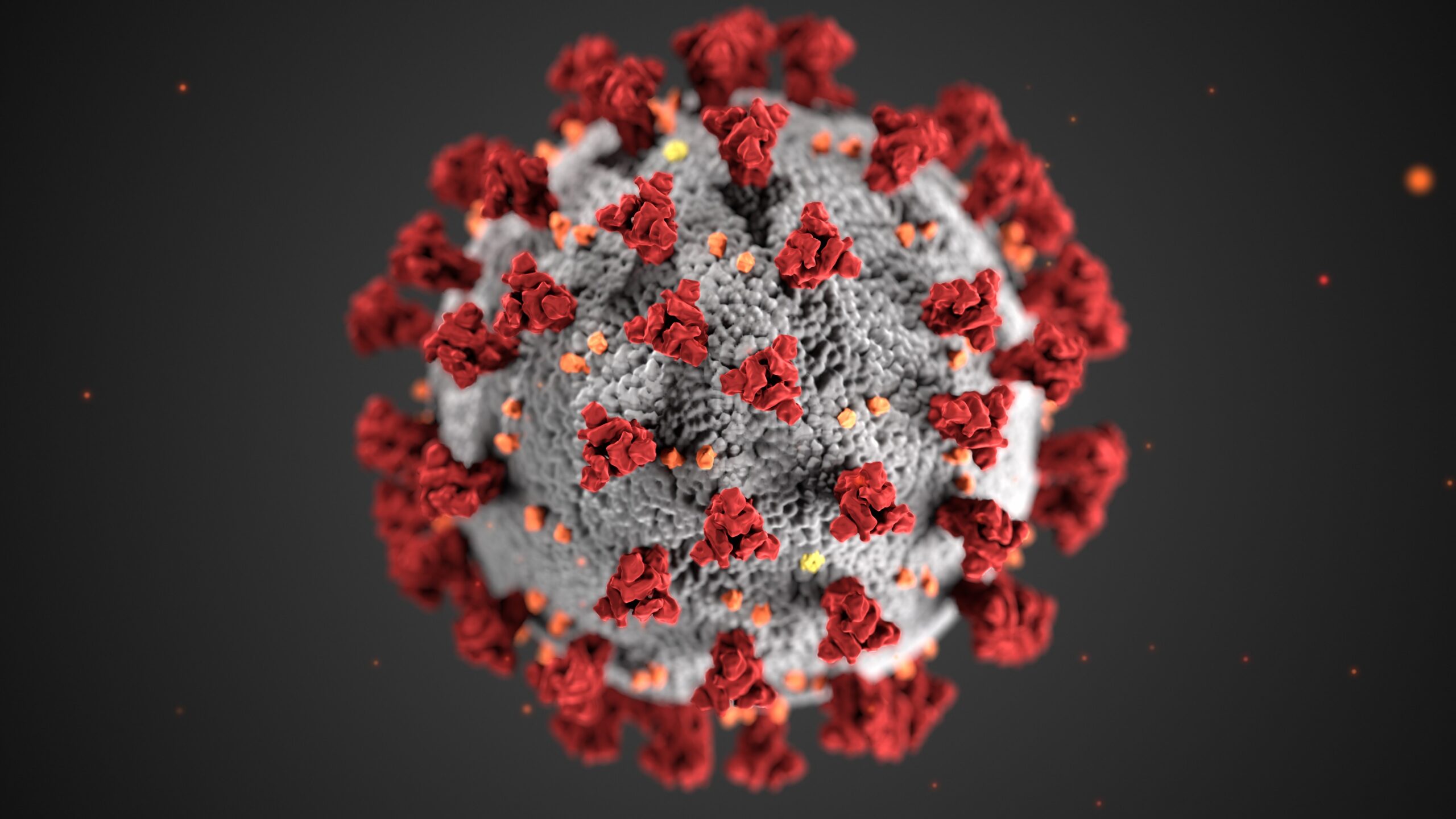

In police records, Ishaq Ahmad Parray is one of 33 young men who have joined the ranks of militancy in the first six months of the year in the Valley, taking the total number of its active militants to 142.Of the 142, 54 are foreigners, mostly from Pakistan, and 88 are local youths. The latter, say the police, is the worrying part.

“The number of local militants has been steadily rising in the past several years, but in the last two years, there has been a sudden spurt. It is a concern because local militants elicit sympathy if they are killed or arrested. Besides, they know the topography better and have a large network of friends and relatives who act as couriers and transporters,” says a police officer.

At the onset of militancy in 1989, and till the mid-1990s, thousands of youths from the Valley had joined militant groups such as the Hizbul Mujahideen. After the mid-’90s, foreign militants, mostly Pakistani, formed the majority. After a lull of over a decade, militancy is slowly making a return, but this time with more locals than foreigners.

Zakir has not been home since July 17, 2013. A civil engineering student at a Chandigarh college, he was home on vacation. That day, he walked out, leaving behind a letter for his father Abdul Rashid Bhat, an engineer employed with the government. “It was a brief letter that talked about the injustice being done to Kashmiri Muslims. He had written about Kashmiri students suffering outside the Valley and felt that jihad was the only solution. I understood where he was headed,” says Bhat.

The father, whose other son is a doctor and daughter a bank executive, says that the Zakir who left wasn’t the child who, until then, had “everything he wanted”. Or had excelled at carrom and participated in two national junior-level tournaments.

“He was a spendthrift. Everyday, he would take Rs 200 for ice cream and chocolates. He wanted to set up his own construction company,” Bhat says.

Last December, Zakir paid a surprise visit home when his grandfather passed away. Once clean-shaven, he now sported a beard and wore combat uniform. “He came, wept for a few minutes and left. Immediately after, an Army officer arrived looking for him. When I told him that Zakir had come and wept for a few minutes, he said, ‘He is a tiger, why would he weep?’.”

Police trace this new trend back to 2010. That year, as young boys in Kashmir had pelted stones at the Army, expressing rage over an alleged fake encounter that had killed three young men, the Army had responded with bullets, killing over 110 youths. Since then, says a Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), “the first signs of local boys joining the militant ranks began showing up”.

“Many friends or relatives of a protester killed in 2010 developed close ties with militants or joined their ranks.

Several boys who were picked up or charged with stone-pelting those days later took to the gun,” he says.

Altaf Khan, the SP of Shopian in south Kashmir, says there is a need to understand the radicalization of youth “due to underlying factors”.

Before 2010, the authorities believed they had turned the corner. Between 1996 and up to the early 2000s, many Kashmiris who had joined the militant groups had called it quits and set up Ikhwan, a counter-insurgency group that worked with the police and Army. With the Hizbul Mujahideen weakened, Pakistani terror group Lashkar-e-Toiba had arrived on the scene and taken center-stage.

Something else has changed: this latest phase of militancy has its base in south Kashmir.

Until now, north Kashmir had been the traditional base of militants in the Valley. Of the 33 youths who joined militancy in the first six months of this year, 30 were from the south, three from the north, and none from the central part. While the total number of militants is still the largest in the north — 69 — only 25 of them are local youths and the rest foreigners. The south, which has 60 militants, has no foreign and only local presence, SSP said.

Leave a Reply